April 3, 2017 — Stocks of predatory fish may be less affected by the catching of their prey species than has previously been thought, according to new research published on April 3.

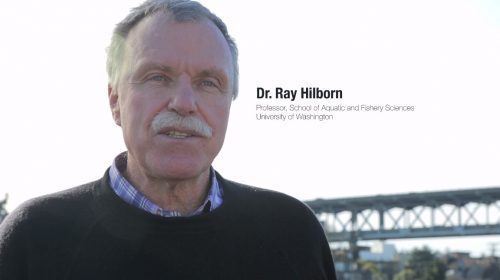

The study – published in journal Fisheries Research and led by well-known University of Washington professor Ray Hilborn – suggests previous studies on this topic overlooked key factors when recommending lower catches of “forage fish”.

Said forage fish include small pelagic species, such as anchovies, herring and menhaden.

The team of seven fisheries scientists found that predator populations are less dependent on specific forage fish species than assumed in previous studies, most prominently in a 2012 study commissioned by the Lenfest Ocean Program, which is managed by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force at that time argued that forage fish are twice as valuable when left in the water to be eaten by predators, and recommended slashing forage fish catch rates by up to 80%.

For fisheries management, such a precautionary approach would have a large impact on the productivity of forage fisheries. As groups such as IFFO (the Marine Ingredients Organisation) have noted, these stocks contribute strongly to global food security, as well as local and regional social and economic sustainability.