April 29, 2013 — In the year 2000, Bob Wood got his doctorate and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (or AMO) got its name. This ocean cycle brings several decades of warming waters followed by several decades of cooling waters in the Atlantic basin. A dozen years after it was named, the AMO remains loosely described and its effects widely debated.

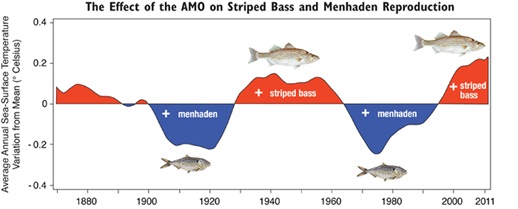

The temperature swings can be small, but the cycle seems to have far-reaching effects. An earlier warm phase of the AMO has been tied to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s and the droughts of the 1950s. Since the early 1990s, the AMO has been in a warm, positive phase — and we've seen twice as many big hurricanes, including Isabel, Ivan, Katrina, and Sandy. We've also seen some boom years for new stripers.

Wood's theory can't tell you whether next year will bring a lot of stripers. "The AMO is a general tendency," says Wood. It can tell you the probability that a warm decade will bring more big storms and those storms will bring more boom years for stripers.

And it can tell you why good years for stripers can lead to poor years for menhaden. All those storms and wind patterns that supply food for stripers can scatter the offshore larvae of menhaden and other coastal spawners, making it more difficult for them to move off the ocean and into the estuary.

When the AMO shifts into a cool phase, menhaden do much better. Cooler temperatures create frequent high-pressure fronts, leading to fewer storms, calmer weather, and easier passage for fish moving out of shelf waters and into the estuary. The menhaden picture is still fuzzy, in part because it's difficult to monitor the offshore migrations of all those shelf-spawning fish. "I'm not sure we've nailed down how most of these critters make it into the Bay," says Wood. That will take a lot of old-fashioned, on-the-water sampling cruises out in the rolling waters of the coastal ocean. Wood has no plans to be aboard.

Read the full story at Chesapeake Quarterly