WASHINGTON (Saving Seafood) – April 3, 2017 – A new study published today in Fisheries Research finds that fishing forage fish may have a smaller impact on their predators than previously thought. The study, authored by a team of marine scientists led by renowned University of Washington fisheries expert Dr. Ray Hilborn, calls into question previous forage fish research that may have overestimated the effect of fishing of forage fish on their predators.

WASHINGTON (Saving Seafood) – April 3, 2017 – A new study published today in Fisheries Research finds that fishing forage fish may have a smaller impact on their predators than previously thought. The study, authored by a team of marine scientists led by renowned University of Washington fisheries expert Dr. Ray Hilborn, calls into question previous forage fish research that may have overestimated the effect of fishing of forage fish on their predators.

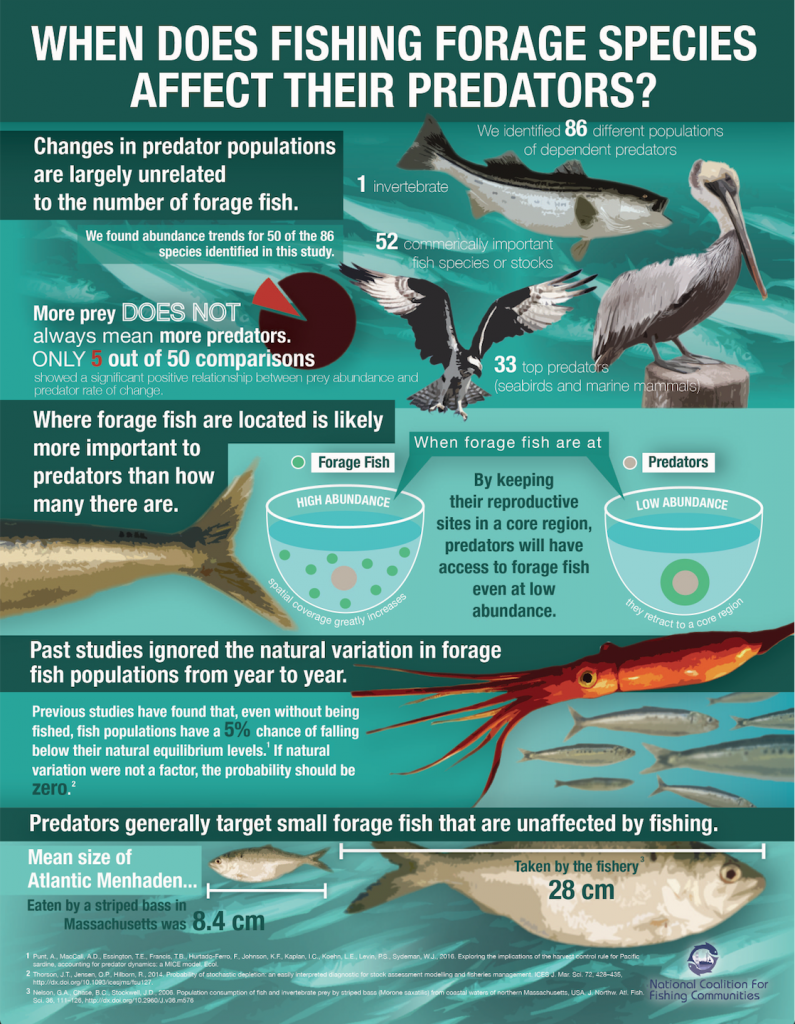

The study, “When does fishing forage species affect their predators?,” finds that changes in predator populations are largely unrelated to the abundance of forage fish. It also shows that the distribution of forage fish is more important to predators than their overall abundance, and that many predators prefer smaller forage fish that are largely unaffected by fishing. Based on these results, the authors recommend that forage fishing policies be created on a case-by-case basis.

The paper’s findings point to issues with previous forage fish research, most notably a five-year-old study funded by the Lenfest Ocean Program, managed by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which it says failed to consider important variables like the spatial distribution of forage fish. Arguably the largest oversight in past research was the high natural variability of forage fish populations, even in the absence of fishing, the authors write.

“There is little evidence for a strong connection between forage fish abundance and the rate of change in the abundance of predators,” the authors write. “The fact that few of the predator populations evaluated in this study have been decreasing under existing fishing policies suggests that current harvest strategies do not threaten the predators and there is no pressing need for more conservative management of forage fish.”

The authors suggest that the lack of a strong relationship between forage fish and their predators is the result of “diet flexibility” – the idea that predators can switch between prey species, helping them defend against the high natural variability of forage fish populations.

This finding contradicts the widely reported conclusions of the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force in 2012. The study, “Little Fish, Big Impact,” claimed that forage fish are twice as valuable to humans when they are left in the water, rather than fished, because of their great importance to predator species. Based on this conclusion, the Lenfest group recommended cutting forage fish catch rates across the board by 50 to 80 percent.

But Dr. Hilborn and his coauthors advocate for a more nuanced approach, writing that previous models “were frequently inadequate for estimating impact of fishing forage species on their predators” and that “a case by case analysis is needed.” The team explicitly calls into question the Lenfest study’s recommendations, which it says are “not appropriate for all species.”

“Relevant factors are missing from the analysis contained in [the Lenfest] work, and this warrants re-examination of the validity and generality of their conclusions,” the authors write. “We have illustrated how consideration of several factors which they did not consider would weaken the links between impacts of fishing forage fish on the predator populations.”

These missing elements include how fishing mortality compares with the natural variability of forage species, the spatial structure of forage fish populations, and the overlap between the sizes of forage fish eaten by predators and size taken by the fishery.

“It must be remembered that small pelagic fish stocks are a highly important part of the human food supply, providing not only calories and protein, but micronutrients, both through direct human consumption and the use of small pelagics as food in aquaculture,” the paper concludes. “Some of the largest potential increases in capture fisheries production would be possible by fishing low trophic levels much harder than currently.”