April 21, 2014 — Thousands of recreational, charter, and commercial fishermen finally realized that, regardless of disagreements about allocation, we had far more in common than not and that the only way that we were ever going to change the federal management system is by working together.

An oldie but goodie!

I wrote the column below over six years ago. Since then we have gone through two demonstrations in Washington, DC that were enthusiastically supported by recreational, party/charter and commercial fishermen. Thousands of fishermen finally realized that, regardless of disagreements about allocation, we had far more in common than not and that the only way that we were ever going to change the federal management system is by working together (I’ll add here that a subtext of what has become an ongoing dialog deals with the fact that, given higher catch levels and more flexible management, many of our allocation difficulties might simply evaporate.)

Have we been successful? Not hardly, unless the fact that some fishermen are still fishing and some fishing dependent businesses are still in business is success.

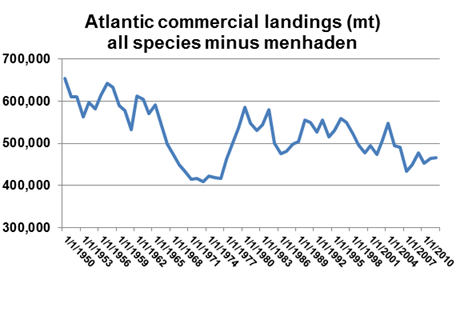

The chart below shows total commercial landings on the US Atlantic Coast from 1950 to 2012 (I excluded menhaden, a fishery which is so large that its inclusion would have distorted what’s happening with our other commercial fisheries).

Needless to say, those supposed rewards of increased harvests when the stocks “rebounded” thanks to the fishermen’s sacrifices haven’t yet appeared, even though most of our stocks are in better shape than they have been in for decades – and those that aren’t are in “bad” shape because warmer sea temperatures have caused them to seek more hospitable areas to the north.

And if you suspect that the slight uptick starting in 2008 or so is indicative of a general trend, bear in mind that the landings have only been reported up until 2012. This was before some pretty significant cuts were (once again) inflicted on the New England groundfish fleet.

As anyone who is reading this can attest, it’s no different for the recreational fisheries.

We didn’t get done what needed to be done in Washington in 2010 or 2012. But things might be looking up. Congressman “Doc” Hastings, Chairman of the House Resources Committee, has been circulating a draft Magnuson Reauthorization package that addresses some of the most egregious outrages that have been inflicted on fishermen by the anti-fishing ENGOs and the handful of fishing industry “leaders” who have joined their camp, and journalists in the popular press, at least those who haven’t partaken fully of the blame-it-all-on-fishing Kool Aid, are starting to look behind the Pew/Oceana media blitzes (for a great example, see John Lee’s Time to rethink fisheries management in The Providence Business News at http://pbn.com/Time-to-rethink-fishery-management,96247).

It’s going to take a significant and focused effort to turn the Magnuson Act back to the supportive legislation it once was, with meaningful roles in federal fisheries management by scientists, managers and fishermen, with research that is equal to the tasks that it is expected to perform, and with safeguards in place that protect both the fish and the fishermen.

It can happen, but don’t believe it’s going to happen without your support and your participation. Find out who the appropriate staffers are in your Senators’ and your Congresswoman’s/man’s office and let them know what you need as a fisherman or as someone who owns or is employed in a fishing dependent business, and that the federal fisheries management system was never designed to protect the wellbeing of the fish while totally ignoring the wellbeing of the fishermen. That’s where we’ve been for most of two decades, and look where it’s gotten us.

<><><><><><><><><><>

It's time to stop Magnuson from being a weapon against fishing communities

by Nils Stolpe

(From Another Perspective on the Saving Seafood website – https://www.savingseafood.org – on December 8, 2009)

A reduction in sea scallop landings of thirty percent. A total closure of the Gulf of Mexico recreational amberjack fishery. A reduction in spiny dogfish landings of twenty-five percent. A total seasonal closure of the recreational sea bass fishery in the Northeast. A total closure of the red snapper fishery in federal waters from Florida to North Carolina. Recreational summer flounder restrictions that have decimated the for-hire fleet. Massive West coast rockfish closures based on less than adequate science. A looming lobster bait crisis stemming from a massive though biologically unnecessary reduction in herring landings. One hundred and thirty thousand tons of uncaught groundfish TAC. A labyrinth of MPAs off California established wherever catchable fish are found. And the list could go on, and on, and on….

These are either proposed, recently instituted or ongoing management initiatives, initiatives being imposed on fishermen who are looking at fisheries that are healthier today than they have been in decades. In total they are going to cost commercial and recreational fishermen, the businesses that depend on them and fishing communities in every coastal state billions of dollars. The pending sea scallop cutback alone is estimated by industry experts to come with a quarter of a billion dollar price tag and the cost of the red snapper closure will undoubtedly be in the tens of millions. All of those uncaught Northeast groundfish, if caught, would have pumped a billion dollars into the fishing communities in New England.

Those fishermen have been laboring – and suffering – under severe management restrictions for those decades with the understanding that the sacrifices they would make today would be more than justified by the rewards they would reap in the future. Well, judging by the status of the stocks the future is finally here but judging by the foregoing list of management actions the rewards definitely aren’t.

Are you starting to detect a subtle trend here, or perhaps one that’s not so subtle?

The Magnuson Act, when passed by Congress in 1976, broke new ground when it established that managing our nation’s fisheries was to be accomplished jointly by scientists, resource managers and resource users – fishermen. It was intended as a tool to enable U.S. fishermen to more effectively utilize those fisheries, something that it was effective, in instances too effective, at doing.

Needless to say, there were teething pains. It’s hard to imagine a new management system that would work from the beginning, and this one didn’t. In the beginning there was a “catch ‘em all” attitude that was probably due more to the Cold War than to fisheries management concerns. Then, starting in 1981, an ill-advised “economic recovery” program by the Reagan administration brought far too much fishing capacity to the domestic fleet than was necessary. Sshortly afterwards, in 1984, the World Court awarded much of the New England fleet’s fishing grounds to Canada. Obviously, in the first decade or so of Magnuson management some fisheries suffered, but external factors were much more responsible than anything intrinsic to the fishing industry or to the management process itself.

But, using these early stumbling blocks as the reason, over the intervening three decades fishermen have been gradually dealt out of the Magnuson process, the scientists have been put in charge, and as the list of closures and restrictions up above painfully demonstrates, the Act has been turned into a weapon that is now being used against fishermen and fishing communities.

How has this been accomplished? Through a well-orchestrated campaign based on what has come to be known in the world of propaganda as The Big Lie – a lie so outrageous and repeated so often that the people will eventually accept it as the truth.

In this case The Big Lie is that fishermen are inherently incapable of sustainably managing the fisheries they participate in. The sole basis of this theory is The Tragedy of the Commons, an article published in the journal Science by an ecologist, Garrett Hardin, in 1968. Hardin’s article describes the dilemma of hypothetical herders sharing a hypothetical plot of land in medieval Europe. It’s been used and is still being used as proof positive that fishermen are incapable of rationally harvesting fish that “belong to everybody.” Hardin is reputed to have said later that his article might better have been titled “The Tragedy of the Unregulated Commons,” which has no bearing at all to today’s over-regulated fisheries. This obvious fact is understandably ignored by the foundation-funded anti-fishing activists in their so far successful campaign to marginalize fishermen in the management process. (Note that this year’s Nobel Laureate, Elinor Ostrom, convincingly – at least to the Nobel selection committee – argues that Hardin’s “tragedy,” though applicable in limited situations, suffers from over-application.)

So with the fishermen on the way out, or at least the independent fishermen who don’t kowtow to Silver Spring or the anti-fishing claque, who’s taking up the slack in the fisheries management process? That would be the scientists that work for NMFS and those on each regional management council’s Science and Statistics Committee. At this point they’re in charge, and their statistics and their computer models, no matter how imprecise, based on their samples, no matter how meager, and their budgets, no matter how inadequate, are what’s determining what we can and can’t (emphasis on the latter, of course) catch. And don’t forget that extra 20 or 30 or 40% “off the top” that is used to make up for the uncertainty of their science.

Those imprecise statistics, meager samples and inadequate budgets are exactly why Congress decided over 30 years ago that fishermen and resource managers should have a major say in fisheries management. The experience and observations of the fisherman and the concern of the managers for the resource users as well as the resource were put there to balance the narrow input of the scientists.

But, thanks to the last two Magnuson reauthorizations, and to what it’s impossible for me to see as anything other than the “let’s get rid of as many fishermen as we can” vibrations emanating from NOAA/NMFS headquarters, that’s no longer the case. The science, no matter how limited, rules and the experience, judgment and concern for the human impacts have become completely irrelevant.

This wasn’t the intention of the Magnuson Act’s authors, it wasn’t the intent of the Congress that passed it, and if they understood how purposefully fallacious this particular Big Lie is and the full extent of the damage it has unnecessarily caused and continues to cause in every fishing community in the U.S., it’s hard to imagine any of our elected officials allowing it to continue. But as we are all too well aware, continue it does.

So what do we do to fix this mess? First off, the members of every aggrieved recreational or commercial fishery, and name more than one or two in the lower 48 that aren’t, have to realize that the most serious of their problems begin and end with the purposely mutated monster that Magnuson has become. Then, as members of that fishery, they have to make the demand that Magnuson be returned to its former state, once again with the balance for the inadequate science provided by the judgment of fishermen (nominated and approved by their peers, not forced on the system by the palace guard in Silver Spring) and resource managers. And finally they – but at this point it’s we – have to set aside our differences and come together, along with all of the associated businesses and organizations and individuals that have a stake in viable fisheries, in the effective lobbying power that we should be, and start to get the job done.

This is a process that’s already started, both in Congress and with a number of fishing organizations. But it’s not going to succeed without your support and your participation. You can start off by demanding that your reps in Washington join Congressman Barney Frank’s East Coast congressional caucus, which he plans on starting within two weeks to organize “an uphill battle against environmental forces to create a more equal balance between the reconstruction of fish stocks and community interests.” And there are other, industry-focused efforts in the works as well. Do everything you can to get them and keep them going. I’ll keep you posted to the extent that I can, but remember that ultimately it’s up to you.

In keeping with the season, they’re your chestnuts and you’re the only one that’s going to get them out of the fire that we’ve allowed to burn for way too long.