WASHINGTON – 13 March 2013 — On February 20, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support claims that menhaden are overfished. The full ASMFC approved a report adapted from a January 2013 Menhaden Technical Committee teleconference which determined that based upon currently-available information, the status of the resource is unknown and will remain so until a new stock assessment is conducted.

Leading up to last December’s highly-charged and emotional ASMFC meeting when new regulations on Atlantic menhaden were adopted, numerous conservation and recreational fishing groups made the claim that the stock was overfished, dismissing scientific arguments to the contrary, and disparaging evidence presented by the commercial fishing industry. These groups included the Coastal Conservation Association, the National Coalition for Marine Conservation, and in several instances, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, whose senior scientist Chris Moore wrote in December that the “Menhaden Technical Committee says that if the new population standards it recommends are adopted, the population would be considered overfished."

One particularly high-profile appearance of the claim was in a November 2012 letter to the ASMFC signed by 94 “scientists,” many of whom had affiliations with the Pew Environment Group. Few if any of the signers had actual experience in menhaden stock assessments and one of the “scientists” is an English professor. In the letter, the group alleged that “the best scientific information we have indicates that menhaden is subject to overfishing and is overfished when evaluated against a 15% MSP biomass threshold.” Citing this letter, Pew’s Northeast Fisheries Program Director Peter Baker wrote, in a December 2012 op-ed, “the stock is thus overfished according to the most recent science,” and argued that the commercial industry’s position, which has turned out to be true, was “an outdated picture of the science.”

The claim that menhaden are overfished was echoed in media outlets, both national such as the New York Times (“Battle Brews Over a Small, Vital Fish,” 12/13/12) and local, such as the Newport News (Virginia) Daily Press (“New draft plan to manage menhaden,” 9/18/12).

All of these claims were made — and reported — before the facts were in.

The Determination of “Overfished” Status

“Overfished” is a regulatory determination, not a scientific concept. A population of fish reaches overfished status when the stock falls below a threshold set by regulators. This threshold, called a reference point, is set by fishery managers in consultation with scientists in an effort to determine levels at which fish stocks are healthy.

At the ASMFC meeting in December, not only were harvest cuts made to the menhaden fishery, but the reference points for the species were lowered. Many observers incorrectly anticipated that under the new reference points, the previous years’ fishing efforts would be determined to be in an overfished status. In fact, during the December meeting, even the Board’s Chair, Louis Daniel of North Carolina, stated that menhaden “is most likely overfished based on the newly adopted reference points.” However, when the Atlantic Menhaden Technical Committee met via teleconference on January 25 to revisit the status of the stock, they reviewed the scientific evidence, and found the situation was not as clear-cut as many assumed. “I don't believe anybody is able to make that call at this point," said Committee member Amy Schueller. The committee came to the conclusion that there was insufficient evidence to label the menhaden stock as overfished, noting that there was too much uncertainty in the data.

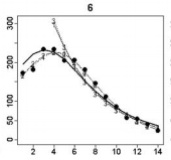

When scientists evaluate stock size estimates, they run assessments with varying data inputs, called sensitivity runs. The results showed disagreement among different sensitivity runs as to whether or not the stock is overfished. One of the variables in the mathematical model is known as “selectivity”. “Selectivity” refers to the likelihood of particular fish being caught by a fishery. This varies within a species based on factors such as age, size, or location. The age assumptions used in the model can be charted on a “selectivity curve,” quantifying and comparing the extent to which different age groups within a species are susceptible to fishing.

The data used in assessing menhaden populations come primarily from fishery landing data, not from random scientific surveys. This is the result of funding decisions made by state and federal regulators. As a result, the fish caught and counted are not a random sample, but instead they are the fish targeted by fishermen. So the statistical model must compensate for the non-random nature of the catch.

Age groups that are most susceptible to being caught are said to have higher selectivity, whereas age groups that are less susceptible to being caught have lower selectivity. The selectivity curve used in the current assessment for menhaden, and a majority of the sensitivity runs, plots each age against its corresponding selectivity value.

Selectivity

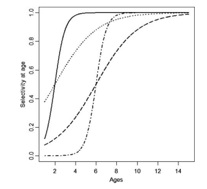

The model run used for one of the selectivity curves, known as a “flat-topped curve” assumes that fish ages one and older are equally likely to be caught by the fishery up to the age of three, at which point the fish are assumed to have been caught. Very few fish age four and older are caught in the commercial menhaden fishery. The selectivity curve pattern plateaus at maximum selectivity, creating a flat top, hence the name of this model. (View an example of a flat-topped selectivity curve from James T. Thorson and Michael H. Prager’s 2010 report in Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, “Better Catch Curves: Incorporating Age-Specific Natural Mortality and Logistic Selectivity” below).

However, this assumption may not reflect actual conditions within the fishery. Menhaden become increasingly vulnerable to being caught as they grow to three years old, and then become decreasingly susceptible to harvest. Fish under the age of one inhabit shallow waters and are not often caught by the fishery, while older fish are not available to be caught because they are in the northern Atlantic waters during the fishing season. So, the true selectivity curve for the fishery may very well take a different shape than the current model.

The majority of the fishery only catches a high proportion of fish in the middle age group of one to three year olds, so selectivity is likely higher for these age groups than all of the others. The increasing propensity of menhaden up to age three to be caught, and their decreasing availability beyond that age creates a curve that is bell-shaped. This is known as a “dome-shaped” selectivity curve (View an example of a dome-shaped selectivity curve from the Thorson report below, age is represented on the x-axis and catch is represented on the y-axis).

Of the base run and the five sensitivity runs analyzed by the Technical Committee during their January conference call, only one used the dome-shaped selectivity curve; and this model – the one that very likely most represents the true selectivity – was the model that indicated that the menhaden population was not overfished.

Since the flat-topped model assumes that the fishery is catching an equal proportion of fish over the age of three, while the evidence indicates the fishery actually catches a declining proportion of older fish, the catch is probably overestimated in the flat-topped model, resulting in the runs that estimated the menhaden population was overfished.

Alexei Sharov, a member of the Technical Committee (TC) from Maryland, spoke during the conference call of the uncertainty between the two selectivity curves: “Since the TC has no means at this point to verify which one is correct, we remain uncertain in that sense,” he said. "Nobody in my mind would be able to say firmly that one run is more believable than another one.”

In their report to the ASMFC’s Atlantic Menhaden Management Board, the Technical Committee stated that “there was not sufficient evidence to determine an overfished status,” and upon reviewing the data, the full ASMFC agreed with the Technical Committee, approving their report.

Last December's ASMFC menhaden meeting was dominated by the charges that menhaden was consistently overexploited, and had the ASMFC adopted the "best available science" the species would clearly be revealed as overfished. But the science available then and now never supported such a definitive claim. The status of menhaden was and remains unknown, and new and better data are needed to effectively manage the future of the species.