Scientists at the Coonamessett Farm Foundation (CCF) in Massachusetts are researching the effects of a fish-killing parasite recently observed in Georges Bank yellowtail flounder populations.

The organism, Ichthyophonus, progressively invades its host’s vital organs, destroying their liver, kidneys, and heart. It generally afflicts older fish in a stock, which are also the most important for repopulation.

The organism, Ichthyophonus, progressively invades its host’s vital organs, destroying their liver, kidneys, and heart. It generally afflicts older fish in a stock, which are also the most important for repopulation.

Yellowtail liver with Ichthyophonus granulomas. Photo courtesy of Dr. Roxanna Smolowitz

Recent surveys from NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center show diminished yellowtail flounder biomass, low recruitment, and a scarcity of older fish in Georges Bank. To help rebuild the population, regulators only allocate a low yellowtail quota. But because yellowtail inhabit the same areas of the water column as many other species with higher quotas, they act as a “choke stock.” Once scallopers and groundfishermen inadvertently reach their yellowtail quota while targeting other species, the whole sector is forced to stop fishing or otherwise risk hefty penalties for exceeding their yellowtail allotment. Even a small amount of yellowtail bycatch can shut down a fishery.

In 2012, Dr. Roxanna Smolowitz, director of CFF and the Roger Williams Aquatic Diagnostic Laboratory, collaborated with colleagues Carl Huntsberger, Kathryn Goetting, and her husband, Captain Ron Smolowitz, to test yellowtail after scallopers witnessed some fish in the stock with the parasite in 2011. During the fall, the team performed systematic sampling on yellowtail flounder caught as bycatch in scallop dredges. Their research showed high rates of infestation in older males and females.

The team is continuing their sampling efforts to learn how widespread the parasite is in the yellowtail stock. “We know it is causing mortality,” said Dr. Smolowitz; “we need to find out how severe.” She continued, “When you have a stock that won’t come back, you need to look for other reasons.”

Dr. Smolowitz presented CFF’s research at a May workshop hosted by the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Institute at the University of Massachusetts School for Marine Science and Technology (SMAST). The findings provide scientists and managers a better idea of what pressures outside of fishing mortality are affecting yellowtail stock numbers.

Dr. Smolowitz presented CFF’s research at a May workshop hosted by the Massachusetts Marine Fisheries Institute at the University of Massachusetts School for Marine Science and Technology (SMAST). The findings provide scientists and managers a better idea of what pressures outside of fishing mortality are affecting yellowtail stock numbers.

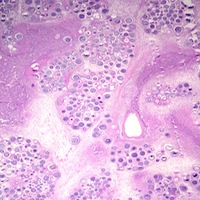

Stained yellowtail liver tissue under a microscope showing hepatitis caused by Ichthyophonus parasite. Photo courtesy of Dr. Roxanna Smolowitz.

Currently, managers determine commercial catch limits based on fishing mortality and an estimate of natural mortality. That natural mortality estimate, however, may not fully account for the lethal effects of parasites. According to Captain Ron Smolowitz, treasurer of CFF and a retired NOAA Corps officer, before managers can include this new information into their assessment model, they need to learn if these parasites are new to the yellowtail stock, and if not, if their levels have increased. “These aren’t things that are easy to learn,” he said. “All we have now is information from one point in time."

CFF’s preliminary research shows promise to improve current yellowtail management. “If we understand what’s happening, it gives us more information to know how to deal with the stock,” said Dr. Smolowitz. “We have to know what is affecting the population before we can properly manage them."

The research team is continuing their efforts to learn more about these parasites and how they affect yellowtail populations. Dr. Smolowitz says they know that the parasites can spread through the yellowtail’s food source, but they do not know if they can also spread openly in the water column. CFF is also trying to determine what variables — such as habitat, climate change, fishing pressure, and natural parasitic cycles — affect the parasite. Ichthyophonus has been documented in many species including winter flounder, rainbow trout, Atlantic cod, and since 1916 has been detrimental to Atlantic and Pacific herring populations

Members of the media may contact Dr. Roxanna Smolowitz at rsmolowitz@rwu.edu or 401-254-3299.