May 20, 2014 — Greenhouse gases, sea level rise, energy crisis, factory-farmed meat, deforestation, oil spills, the dead zone in the Gulf – man, we’ve really messed up the environment. At least, that’s what many news-savvy Americans tend to believe. We’re still figuring out what damage is irreparable and what parts can still be salvaged. But in the face of all this gloom, there’s a scaly, smelly glimmer of hope: the fish.

For over a century, the major bodies of water surrounding the United States were drastically overfished. “Prior to 1976, there was no federal legislation that managed U.S. fisheries,” says Ted Morton, the director of Federal US Oceans at the Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonprofit environmental organization. “Fishing was going on, but there was no management system in place that was encompassing all of US waters.” As a result, many groups of fish, like the famous cod or the popular red snapper, were depleted beyond sustainable levels.

Starting in 1997, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) began tracking the status of fish populations with the help of various research institutions and fisheries. What they found was somewhat startling: not only were the vast majority of fish populations overfished, but there were significant regional differences between the east and west coasts.

Knowing the Score

Starting in 2005, NOAA assigned a number to each “fish stock”– a group of single fish species that is considered reproductively independent– to assess its overall health. That number, called a

Fish Stock Sustainability Index (FSSI), ranges from 0 to 4 to indicate the fish’s population and known status. If a stock has a higher FSSI number, it is generally in healthier shape and less subject to overfishing. NOAA issues quarterly reports in collaboration with a number different research institutions around the country .

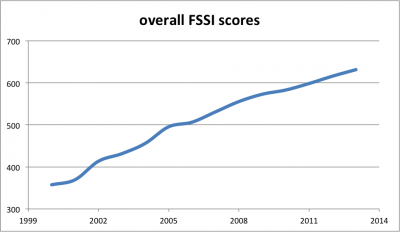

Armed with the FSSI, NOAA started setting annual catch limits for each fish stock, measured by weight. This has been the most successful attempt to oversee a universal reduction in overfishing, says Karen Greene, a representative from NOAA’s Office of Sustainable Fisheries. Since 2000, overall FSSI scores have almost doubled.

Data courtesy of NOAA

Researchers toiled over the past few decades to determine how to keep fish populations sustainable – just how many fish can be removed so that the stock’s reproductive members can keep the population stable. But according to Greene, the process hasn’t been smooth; the initial catch limits are still “a very crude tool” for researchers to understand how much a stock is being overfished.

Coastal Debate

While administrators on the East Coast have spent years tinkering with their catch limits, the West Coast and Alaska already had a leg up in making their stocks sustainable because, according to Greene, catch limits have been in place for a long time. “They have highly productive fisheries there, so they don’t have chronic overfishing problem like in New England,” she says. NOAA biologist Kristan Blackhart agrees, crediting the region’s success to the directors’ focus on streamlining the stock assessment process and reducing bureaucratic excesses.

The NOAA report for the last quarter of 2013 shows that FSSI scores of fish stocks in the Pacific are just slightly higher than those of Atlantic stocks.

Total FSSI

Atlantic: 325.5

Pacific: 168.5

Total number of entries

Atlantic: 125

Pacific: 63

Average FSSI score

Atlantic: 2.604

Pacific: 2.675

Although the scores are almost equal now, the scores from the East Coast have changed more dramatically in the past decade because those stocks had been overfished longer than any other ocean around the U.S. “There is a longer history of fishing in Northeast, ” Morton says. “It’s really been centuries of effort, even prior to colonial times.” Despite significant progress, many fish stocks are still overfished.

Read the full story at Science Line