SEAFOOD.COM NEWS by John Sackton — July 25, 2013 — Because of the diversity and nature of the seafood industry, few corporate brands have achieved the power of the geographic brands. Unlike cars, for example, where a brand like Mercedes can be made outside of Germany and still retain its value, seafood producers are much more tied to specific geographic areas.

A number of Alaskan companies are considering what steps they should take to defend their brand in the face of active opposition to sales of Alaskan products that are not ‘approved’ by NGO’s.

This has come about because of the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership’s attempt to tell its partners, including Walmart, not to buy Alaskan products.

The reasons have nothing to do with sustainability, and everything to do with maintaining the role of the SFP as a gate keeper or arbiter of which seafood products should be purchased and which should not.

The actions of organizations like SFP and the MSC are direct threats to the brands established by the major seafood producing regions.

Consumer perceptions of seafood – both positive and negative – depend heavily on the origin of the product. The Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute (ASMI) has leveraged this with the most extensive marketing and advertising campaign around seafood in the U.S. In Norway, the Norwegian Seafood Export Council, now called the Norwegian Seafood council, has followed a similar path.

Successful producing regions that have proved themselves capable of long term sustainability, high quality and consistency, have established a market reputation that enhances the value of their products. In short, there is a premium that buyers pay for a consistent quality seafood brand.

Because of the diversity and nature of the seafood industry, few corporate brands have achieved the power of the geographic brands. Unlike cars, for example, where a brand like Mercedes can be made outside of Germany and still retain its value, seafood producers are much more tied to specific geographic areas.

This is because the particular fish stocks, management, and harvesting and processing all depend on a geographic area. Remove the geographic distinction, and a portion of the premium value disappears.

Examples of these regional brands are Alaska, Norway, Iceland, Chile, New Zealand, and Maine. All these producing regions, with varying degrees of success, have attempted to use the geographic brand to enhance the value of their fisheries.

Reducing the output of these fisheries to a simple MSC label – yes or no – allows seafood buyers to take away the ‘brand’ and its premium.

Alaska salmon is more expensive than Russian salmon because of this brand premium. Yet Walmart made a conscious decision, largely due to price, to remove “alaska” from the descriptors on all but one of its frozen salmon products. Instead they use the term ‘wild’, allowing them the ability to purchase less expensive products, but depriving customers of a choice to buy Alaska products. Interestingly, Walmart has made no such attempt in its canned goods department – where use of the Alaska brand is widespread.

To try and quantify the impact of geographic brand, we partnered with Food Genius, a relatively new company that maintains a database of over 100,000 U.S. restaurant menus, representing about 56% of the US restaurant universe. FoodGenius data covers over 300,000 separate restaurants.

They sell data analysis to the restaurant industry so operators can test concepts, descriptors, price points etc.

For example, their salmon data looks like this:

It shows that 39% of US menus have a salmon item.

The most popular preparation is ‘Grilled’, with 46% of all menus offering a grilled salmon item The second most common descriptor was ‘Fresh‘ with 32% of the menu mentions.

The average price of "salmon" dishes are $12.12 nationwide, with other popular price points being $10-11 (8%, $12-13 (7%), and $6-7 (7%). Of the 39% of menus that have "salmon", 52% are located at Independents, and 48% are chains. And 80% of the menus have an average price of entrees between the $7-12 or $12-20 range – (Restaurant Segment = $, $$).

We wanted to take this database and see if we could measure descriptors of geographic brands.

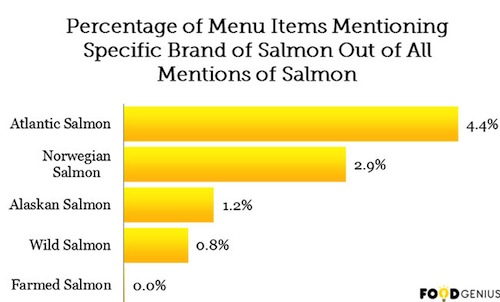

Here are the results for salmon:

Source: Foodgenius database

Atlantic salmon is mentioned by name on 4.4% of salmon menu items, while Alaska salmon is mentioned by name on 1.2% of salmon menu items. Interestingly Norwegian salmon is mentioned on 2.9% of salmon menu items, as this is an important way to distinguish Atlantic salmon.

We also looked at Cod. Here, the main preparations were dominated by fried (32%) and filleted (24%). Fresh cod was on 15% of the cod menu items.

With cod, the Alaska brand was the most mentioned.

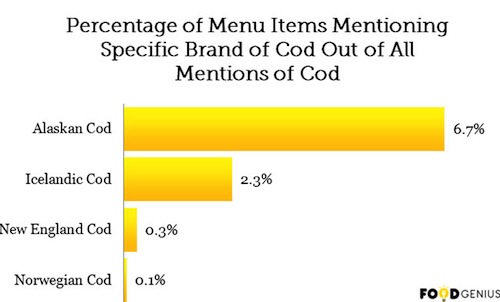

Source: Foodgenius database

Nearly 7% of cod menus specifically listed Alaskan cod, with 2% listing Icelandic cod.

When we looked at other items, with the exception of Maine lobster where Maine had a 4.7% of lobster menu item recognition, there was very low recognition of other geographic areas.

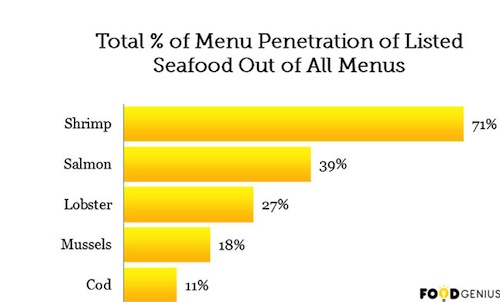

Source: Food Genius data

Shrimp was on 71% of all restaurant menus – more so than salmon, but "Gulf" shrimp did even break 1%.

The data from FoodGenius suggests that at foodservice, there is still a lot of room to grow brand recognition.

To the extent that large foodservice chains – like Aramark and Sodexo, and distributors like Sysco, begin to adopt NGO based vetting strategies – i.e. saying they will only purchase NGO approved seafood, this is a clear threat to brand building from the producing regions.

The long term solution here is to engage in public education about sustainability in the same manner as food safety. In the U.S. the public has a high level of trust in the federal government to monitor and regulate food safety. Sustainability is also something that is built in to US law, but is a threat to outside NGO’s to the extent that the US, or the state of Alaska, can achieve long term sustainability without participating in ‘improvement projects’ or certifications dictated by the NGO’s.

This story originally appeared on Seafood.com, a subscription site. It it reprinted with permission.