WASHINGTON (Saving Seafood) 13 March 2013 — The Conservation Law Foundation’s Sean Cosgrove, in a recent post on CLF’s “Talking Fish” website, was critical of the New England Fishery Management Council’s proposals to change closed habitat areas off New England. However, Mr. Cosgrove’s post ignores the credible science backing the proposals. Accounting for new management practices and updated science, the Council has concluded that the boundaries of these closed areas can be changed to the benefit of marine habitats. A comprehensive analysis on the effects of proposed changes, examined by the Council’s Science and Statistical Committee, determined that opening parts of these areas to fishing (including trawling) would minimize the total adverse effects from fishing in this region.

Several peer-reviewed studies published in the last decade conclude that the impact of trawling in these areas is insignificant in comparison to natural events, which often produce forces equivalent to hurricane winds on land. Additionally, recent data that were not available when these closures were first enacted in the 1990s indicate that the boundary lines of many of the closed areas are not in locations best suited for habitat protection. For that reason revisions to these boundaries are both appropriate and needed.

Academic sources used in the preparation of this response are linked throughout and listed in the bibliography at the end of this alert. In the article, “Destructive Trawling and the Myth of ‘Farming the Sea’,” Conservation Law Foundation's (CLF) Sean Cosgrove argues against the New English Fishery Management Council's (NEFMC) recent recommendation to change certain areas previously closed to fishing, claiming that trawling, in every instance, is detrimental to ocean habitats. But Mr. Cosgrove cites incomplete and unrelated evidence in order to argue that marine scientists "unanimously" agree with his allegations. In reality, Mr. Cosgrove's claims are contradicted by numerous peer-revised studies focused specifically on New England's marine ecosystems.

The Truth Behind Trawling in New England

When it comes to trawling, a method of fishing that involves dragging a net on or near the sea bottom, studies have consistently demonstrated that various marine environments respond differently to fishing disturbances. For successful fisheries management, it is important to consider trawling impacts in the context of an ecosystem’s sensitivity to natural disturbances.

Many of the closed areas off the New England coast– such as Georges Bank– are sandy, gravelly seabed ecosystems that commonly experience strong tides and winter storms. These areas are considered “highly dynamic,” meaning that they are accustomed to natural disturbance. Contrary to Mr. Cosgrove’s allegations, multiple studies (links to which are provided in this response) demonstrate that trawling in dynamic ecosystems has minimal effects on the seabed ecosystem, productivity, and volume of invasive species.

Unlike the European deep-sea environment that Mr. Cosgrove cites as evidence of his claims, which is less dynamic and more susceptible to disturbances, many of the closed areas off the New England coast are relatively shallow locations that are subject to regular tidal currents carrying as much force as hurricane winds on land. These result in substantial seafloor disturbances at least every two weeks.

A 2001-2002 federal survey with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) evaluating the effects of trawls on soft-bottom New England habitats concluded that the effects of trawls were comparable to the effects of natural disturbances. The study found no significant ecological or physiological difference between the seabed communities in areas that have been trawled for over 50 years and areas that have only been disturbed by natural events. A more recent academic study concludes that the effects of dredging are even less than those from natural events.

This is not to say that there are no fishing effects in the highly dynamic sandy New England seabed, but the impacts are often temporary. A NOAA survey on soft-bottom environments in the Massachusetts Bay showed that small-scale disturbances in these habitats can rapidly recolonize in as quickly as a few hours or up to a few days. A 2004 study, conducted by scientists at the University of Connecticut and the US Geological Survey, found that that highly-dynamic ecosystems are likely able to recover from the impact of bottom fishing gear in less than a year.

As for Council Member Laura Foley Ramsden’s question about the benefits of disturbances: this idea is well documented in terrestrial ecosystems, but mostly null in aquatic environments. Still, the idea is not as “inexplicable” as Mr. Cosgrove tries to suggest. One of the first studies on this issue (Rhoads, McCall and Yingst; 1978) noted that disturbed habitats, after being repopulated by near-surface dwelling organisms, were 2-6 times more productive than undisturbed areas of sea bottom. The aforementioned NOAA survey in the Massachusetts Bay found little difference between the trawled and control areas except parts of the trawled areas had slightly higher faunal density.

Though Mr. Cosgrove twice claims that trawling in New England reduces productivity, this conclusion in contradicted by scientific evidence. He cites two sources that actually refute or ignore the claims he makes. The Jennings et al study "Trawling disturbance can modify benthic production processes" concludes that trawling effects on production are consistent with the effects of natural disturbances, and Kaiser et al “Modification of marine habitats by trawling activities: prognosis and solutions" concurs, noting that with low-level trawling, the disturbances will be similar to those from natural factors.

There is also no conclusive evidence suggesting a link between trawls and an increase in invasive species in New England. In fact, in the article that Mr. Cosgrove cites, trawling is never mentioned as a factor. Instead, the author attributes the increased appearance of invasive species to international shipping. In the Gulf of Maine, invasive species mostly come from European trade and transportation vessels, which accidently bring non-native species over in the ballast tank or fouling on the ship.

Lastly, the plumes pictured in the article are not “visible from outer space”, as Mr. Cosgrove claims. The pictures were taken using advanced satellite imaging — the same technology that can photograph items as small as a car’s sunroof. Considering, contrary to the widely accepted lore, not even the Great Wall of China is visible to the naked eye from outer space; the effects of trawling are certainly not.

Under their legal mandate to minimize the long-term adverse impacts of fishing, the NEMFC has undertaken an in-depth analysis to ensure that trawling is managed properly. Proposed management guidelines will regard factors such as seabed ecology, how quickly an area rebounds, and seasonal spawning to determine when, where, and how often fishermen can use trawl nets.

Redirecting the Debate

The recent NEFMC meeting was not about trawling and certainly not about “farming the sea.” The focus was on the Omnibus Habitat Amendment, a plan to open previously protected habitats in such a way as to minimize adverse effects from fishing

Mr. Cosgrove accuses the NEFMC of demonstrating “a lack of regard” for the benefits of protected habitat areas when in fact members have discussed this topic in depth. In a comprehensive analysis that has been praised by the NEFMC Science and Statistical Committee, the Committee concludes that keeping the areas closed is more harmful for the region than if they are changed:

“We find that for nearly all area and gear type combinations, opening existing closed areas to fishing is predicted to decrease aggregate adverse effects. For mobile bottom tending gears, which comprise nearly 99% of all adverse effects in our region, allowing fishing in almost any portion of the area closures on Georges Bank is estimated to substantially decrease total adverse effects from fishing.” (pg. 16)

Under quota regulations, it is a given that a certain number of fish will be caught. What can vary is how far a fisherman will need to trawl in order to catch that quota. So, if fishermen are excluded from fertile fishing grounds, areas where they could catch their quota with less fishing, then ultimately larger swaths of habitat will be affected by gear.

The proposed Amendment recognizes that as fisheries management in the Northeast transforms towards catch-shares management, meaning only a pre-determined quota of fish can be taken from the ocean, opening these productive fishing grounds will have a net positive effect.

The solutions proposed in the Amendment means less seabed and habitat will be affected than if the areas remain closed.

New England also has not witnessed “immeasurable documented benefits,” as Mr. Cosgrove claims, from these closed-off habitats. After almost 20 years of closures and reduced catch allowances, there has been no clear evidence that these closures help groundfish stocks. Many fish populations are continuing to decline. The historic Atlantic cod is still considered overfished in Georges Bank, along with multiple species of flounder, halibut, wolfish, and hake.

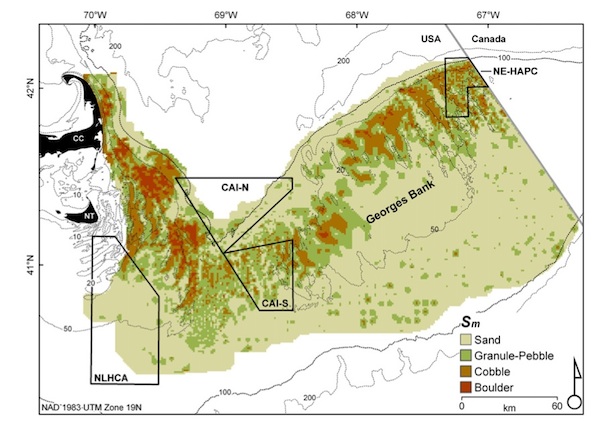

Recent science suggests that these closures fail to protect vital seabed habitats as intended. A 2010 study on the Georges Bank seabed showed that the boundaries (detailed in the included map) do not comport with what the most recent science has uncovered about seabed type. In fact, many rocky locations, which are less dynamic and more susceptible to fishing disturbances, lay outside of the designated areas. This creates a no-win situation for both fishermen and fish as fishermen are driven to fish in rocky areas where they do not want to work (because of damages to trawl gear), and these are the very areas that are likely important to many species.

Additionally, the underlying reasons on which many of these closure determinations were made are outdated. The locations of the “Essential Fish Habitat” closures, created in the late 1990s as part of the Magnuson-Steven Fishery Conservation and Management Act, were based on limited seabed habitat information. In the 1990s, the available information about the geography of the New England seabed contained data with only 100 sample points– compared to the 70,000 sample points available today. The areas were chosen based on the locations of previous management closures from earlier in the decade that were intended to limit fishing ability, not protect specialized habitat.

As Mr. Cosgrove points out, part of one closure in the Gulf of Maine protects a complex habitat of kelp forest on Cashes Ledge. While accurate, the point is moot. Although some changes to the boundaries of the Cashes Ledge closed area are being considered, none of the proposed options would open that complex kelp forest to fishing.

Bibliography:

Harris, Bradley; Cowles, Geoffrey; Stokesbury, Kevin, “Surficial sediment stability on Georges Bank, in the Great South Channel and on eastern Nantucket Shoals,” Continental Shelf Research, Volume 49, September 23, 2012, p. 65-72

Harris, Bradley; Stokesbury, Kevin, “The spatial structure of local surficial sediment characteristics on Georges Bank, USA,” Continental Shelf Research, Volume 30, Issue 17, October 15, 2010, p. 1840–1853

Hvistendahl, Mara “Is China’s Great Wall Visible From Space?” The Scientific American. February 21, 2008

Jennings, S., Dinmore, T. A., Duplisea, D. E., Warr, K. J. and Lancaster, J. E. (2001), "Trawling disturbance can modify benthic production processes." Journal of Animal Ecology, 70: 459–475.

Kaiser, M. J., Collie, J. S., Hall, S. J., Jennings, S. and Poiner, I. R. (2002), "Modification of marine habitats by trawling activities: prognosis and solutions. Fish and Fisheries," 3: 114–136.

Lindholm, James; Auster, Peter; Valentine, Page, “Role of a large marine protected area for conserving landscape attributes of sand habitats on Georges Bank (NW Atlantic),” Marine Ecology Progress Series, Volume 269, March 24, 2004, p. 61-68

NEFMC “Status, Assessment and Management Information for NEFMC Managed Fisheries.” January 10, 2013

NOAA/NMFS Unallied Science Project, Cooperative Agreement, “Bottom Net Trawl Fishing Gear Effect on the Seabed: Investigation of Temporal and Cumulative Effects.” December 2005

Pappal, Adrienne, “State of the Gulf of Maine Report: Marine Invasive Species,” June 2010 p. 1-6

Puig, Pere; Canals, Miquel; Company, Joan; et al., “Ploughing the deep sea floor,” Nature 489, September 13, 2012, p.286-289

Stokesbury, Kevin; Harris, Bradley, “Impact of limited short-term sea scallop fishery on epibenthic community of Georges Bank closed areas,” Marine Ecology Progress Series, Volume 307, January 24, 2006, p. 85-100