WASHINGTON (Saving Seafood) – September 1, 2015 — Fishermen, fisheries managers, and environmentalists agree that the Cashes Ledge region of the Gulf of Maine is home to some of the most important marine environments in New England. These include lush kelp forests and the diverse ecosystem of Ammen Rock. Since the early 2000s, federal fisheries managers have recognized the value of these areas and have taken proactive steps to protect their unique habitats, preventing commercial fishermen from entering the areas and allowing them to develop mostly undisturbed from human activity.

But according to several environmental groups, including the Conservation Law Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, the National Geographic Society, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, such long-standing and effective protections are suddenly insufficient. A public relations, media and lobbying campaign has launched to have Cashes Ledge and the New England Canyons and Seamounts designated a National Monument. While such an effort may seem consistent with the current record of environmental stewardship on Cashes Ledge, such a designation would actually undermine the current management system by removing local and expert input from the process.

The current closures on Cashes Ledge are the result of an open, democratic and collaborative process. Managed by the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC), the protections are the result of extensive consultation with scientists, fishermen, regulators, and other valuable stakeholders in New England. Through this process, the Council built a durable consensus in the region on the need to protect and preserve Cashes Ledge. As a result, no federally managed fisheries are allowed to operate in the area. Only the state-managed lobster fishery is permitted in the region, which is subject to the equally open and public management process of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC).

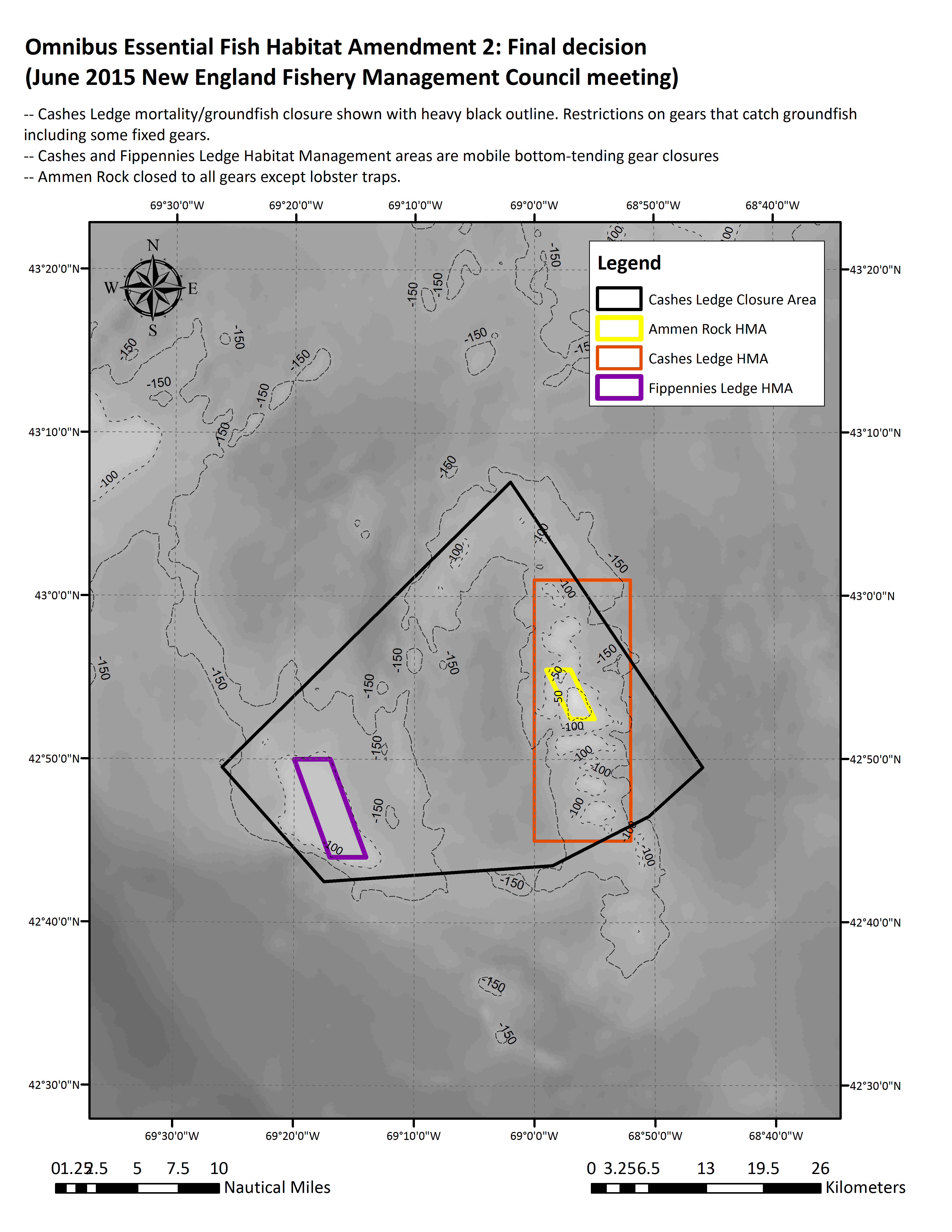

This process has been successful in making Cashes Ledge the hotspot for marine life that it is today. In fact, it has done everything that we usually ask of successful habitat management. The area has been closed for over a decade, and there are no plans to open it in the future. The bottom-tending gear that is likely to disturb habitats is already prohibited in this area. In the recently passed Omnibus Habitat Amendment 2 (OHA2), the Cashes Ledge closures remain untouched, and the current levels of protection are extended into the foreseeable future.

Since 2012, the NEFMC has been working on extending similar protections to the corals and other habitat features of the New England Canyons and Seamounts. Combined with efforts such as NOAA’s Deep-Sea Coral Data Portal, the Council is collaborating with a variety of stakeholders to fashion the best possible protections for the area. On September 23, the Council’s Habitat Committee will be discussing the Omnibus Deep-Sea Coral Amendment. Much like with the habitat protections on Cashes Ledge, this is being conducted through an open and public process that includes scientists, fishermen, regulators, and other interested parties.

So while CLF press secretary Josh Block has been recently quoted as saying a National Monument designation would ensure that the area “remains permanently protected from harmful commercial extraction, such as oil and gas drilling, commercial fishing and other resource exploration activities,” there are no actual attempts to remove the current protections, or to allow any of these activities on Cashes Ledge. Monica Medina of the National Geographic Society, who served in the Obama Administration as Principal Deputy Undersecretary for Oceans and Atmosphere at NOAA, acknowledges that the areas “are currently closed to industrial fishing,” but goes on to say “there have been calls to open them to fishing at some point in the future.” From who is a mystery, because during the OHA2 process, the only suggested openings were for scientific analysis.

National Geographic’s Monica Medina wrote, “scientists have recently uncovered some offshore treasures [in New England]: an area called Cashes Ledge, plus five canyons and sea mounts.” In fact, Cashes Ledge was mapped by R. Rathbun and J. W. Collins in 1887. National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Dr. Sylvia Earle herself acknowledged this after a recent dive, stating, “I saw for myself what scientists have been raving about for years.” And in what turned out to be a harbinger of the National Monument effort, Dr. Earle stated, “Cashes Ledge is the Yellowstone of the North Atlantic.”

In addition to being superfluous to the effective management of Cashes Ledge, a National Monument designation would undermine the management system already in place. A designation of a National Monument necessitates unilateral action by the President under the 1906 Antiquities Act. Such action circumvents and strips away valuable democratic processes that protect these regions and sustain their important commercial fisheries. The council system by which areas like Cashes Ledge are managed – and through which such areas are already off limits to most fishermen – would diminish in importance, as would the expert input from all relevant stakeholders, including scientists, fishermen, and conservationists.

The current management structures and systems now in place under federal guidelines, including the management of the NEMFC and ASMFC, and other regulatory procedures – including proposals to change protections – are fundamentally democratic. They allow ample time for stakeholder input from all perspectives. If organizations such as CLF and the Pew Charitable Trusts want to alter current habitat protections, there is a decades-old, established public process to accommodate them.

These procedures have led to remarkable recent success stories. In fact, just two months ago, both CLF and Pew Charitable Trusts praised the very procedures they now seek to circumvent. In June, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council voted to protect 38,000 square miles of marine habitat to preserve deep-sea corals. The same council process that produced such laudable results in the Mid-Atlantic is the same one that is in place New England. A unilateral marine monument designation, in contrast, would nullify existing management.

Recent history also demonstrates the risks and pitfalls of unilateral attempts to designate marine National Monuments of the exact sort as that being proposed for Cashes Ledge. The expansion of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument by President Obama in 2014, for example, came under intense public scrutiny from native Pacific Islanders, commercial fishermen, and scientists alike, all of whom criticized the Administration for failing to consider crucial stakeholder input.

The current proposal for a National Monument on Cashes Ledge is a solution in search of a problem. It fixes a process that isn’t broken. It seeks an outcome that is already in effect. And it removes the public from the management of public resources.